Documentation

What is COCαDA?

COCαDA (Contact Optimization by alpha-Carbon Distance Analysis) is a tool for calculating intra- and inter-molecular contacts in proteins. COCαDA optimizes the calculation of atomic interactions in proteins, by using a set of fine-tuned Cα distances between every pair of aminoacid residues. The code includes a customized parser for both PDB and CIF files, containing functionalities for handling large files, filtering out specific residues and interactions, and calculating geometric properties such as centroid and normal vectors for aromatic residues.

The contact types available are:

- Hydrophobic

- Hydrogen Bond

- Attractive

- Repulsive

- Disulfide Bond

- Salt Bridge

- Aromatic Stacking

What is COCαDA-web?

COCαDA-web is a user-friendly web interface for using the COCαDA command line tool. COCαDA-web contains a database of pre-calculated contacts for all structures available in the PDB (Protein Data Bank).

Contact rules

| Contact Type | Distance range (Å) | Description | Acronym |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond | 0 ≤ dist ≤ 3.9 | Acceptor and Donor atom pair | HB |

| Disulfide Bond | 0 ≤ dist ≤ 2.8 | Cys:SG atom pair | DS |

| Hydrophobic | 2.0 ≤ dist ≤ 4.5 | Hydrophobic atom pair | HY |

| Repulsive | 2.0 ≤ dist ≤ 6.0 | Equally charged atoms | RE |

| Attractive | 3.9 ≤ dist ≤ 6.0 | Differently charged atoms | AT |

| Salt Bridge | 0 ≤ dist ≤ 3.9 | Equally charged atoms AND hydrogen bonding | SB |

| Aromatic Stacking | 2.0 ≤ dist ≤ 5.0 | Centroids of two aromatic rings in parallel or perpendicular orientation |

AS |

How to use COCαDA-web

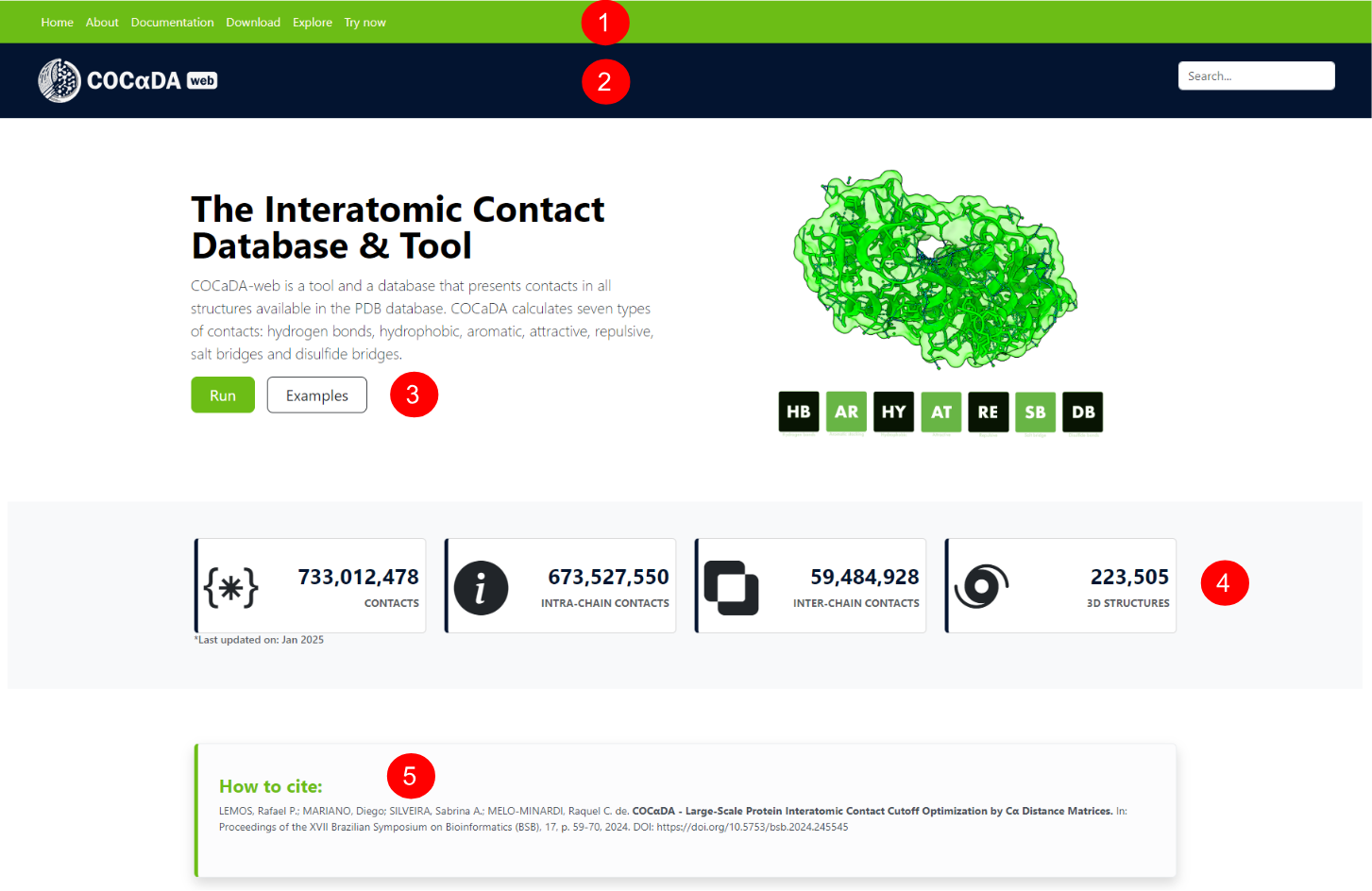

Landing Page

On the upper part of landing page of COCαDA-web, the user can see the navigation bar (1) and the search bar (2). Below, a short description of the tool is given, with the options to run it or see examples (3). There are also database statistics (4), with the total number of contacts, intra- and inter-chain contacts, and the number of processed PDB structures. At the end of the upper part, the user can see the reference for the tool (5).

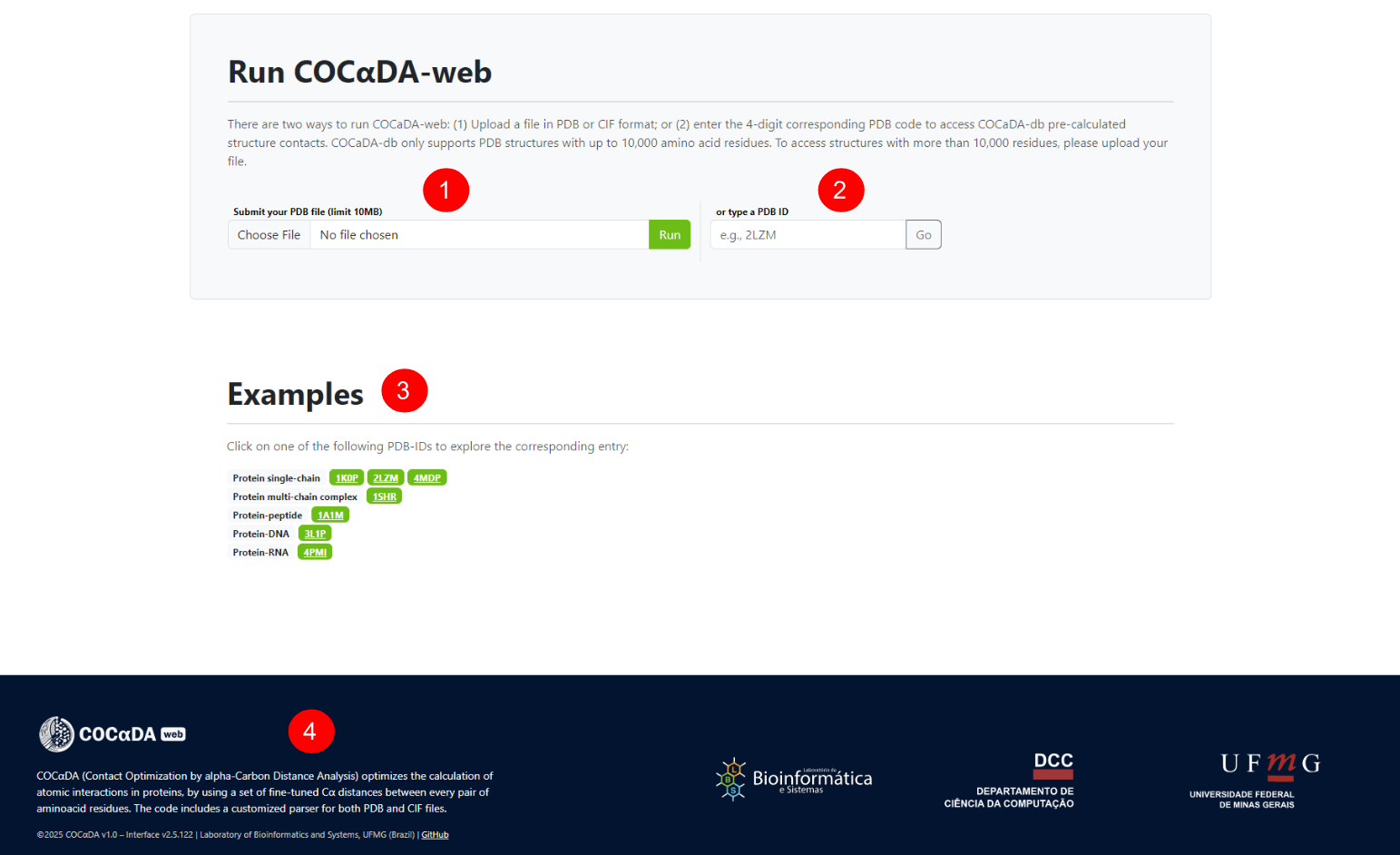

Scrolling down the landing page, or clicking on the "try now" button on the navigation bar and the "run" button on the upper part, the user can see the bottom part of the landing page. There are two ways to use COCαDA-web: through the submission of local .pdb or .cif files (1), or through the PDB ID of the protein (2). Also, there are some examples for different groups of proteins (3), and the current version of the tool (4).

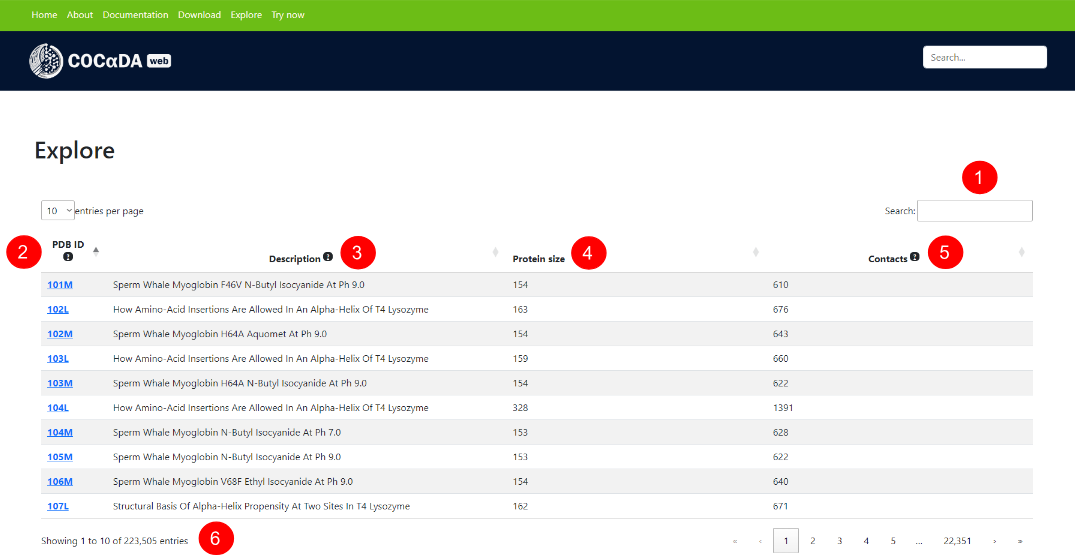

Explore Page

The explore page can be accessed using the "explore" button on the navigation bar, and exhibits a dynamic list of all entries of the database. The user can search specific entries (1), and all columns of the list can be sorted by ascending and descending order. The columns are: PDB ID's (2), description of the proteins (3), their sizes in residues (4), and the number of contacts in their structures (5). The total number of contacts and the results pagination can be seen at the bottom (6).

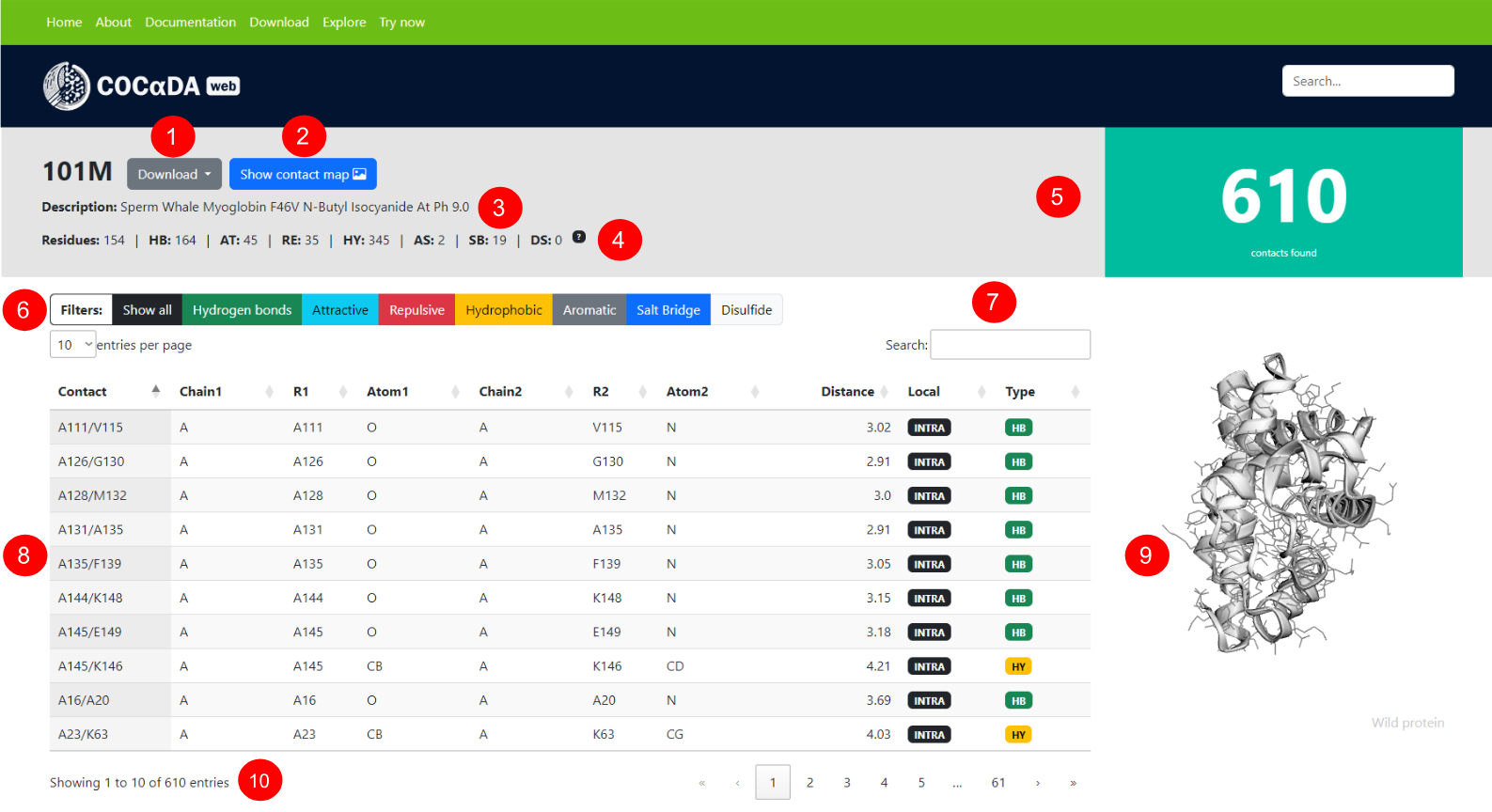

Results Page

The results page for a given protein can be accessed either via clicking an entry on the explore page, or by submitting a local .pdb or .cif file. Using as example the PDB ID 101M, the user can download the results in .csv format (1), see the protein contact map (2), its description (3), the number of contacts of each type (4), and the total number of contacts (5). The results can filtered by contact type (6) or by a specific contact (7).

The list of contacts (8) showcases the full information for each individual contact in the protein, and each column can can be sorted by ascending and descending order. The columns are: contact name; protein chain of the first atom; residue of the first atom; name of the first atom; protein chain of the second atom; residue of the second atom; name of the second atom; distance between the atom pair, in angstroms; localization of the contact (intra-chain or inter-chain); and contact type.

A dynamic and interactive visualization of the protein can be seen on the right-hand side of the page (9), reflecting the selected contacts on the results list. On the bottom of the page (10), the user can see the total of contacts present in the current filter, as well as the pagination of the results.

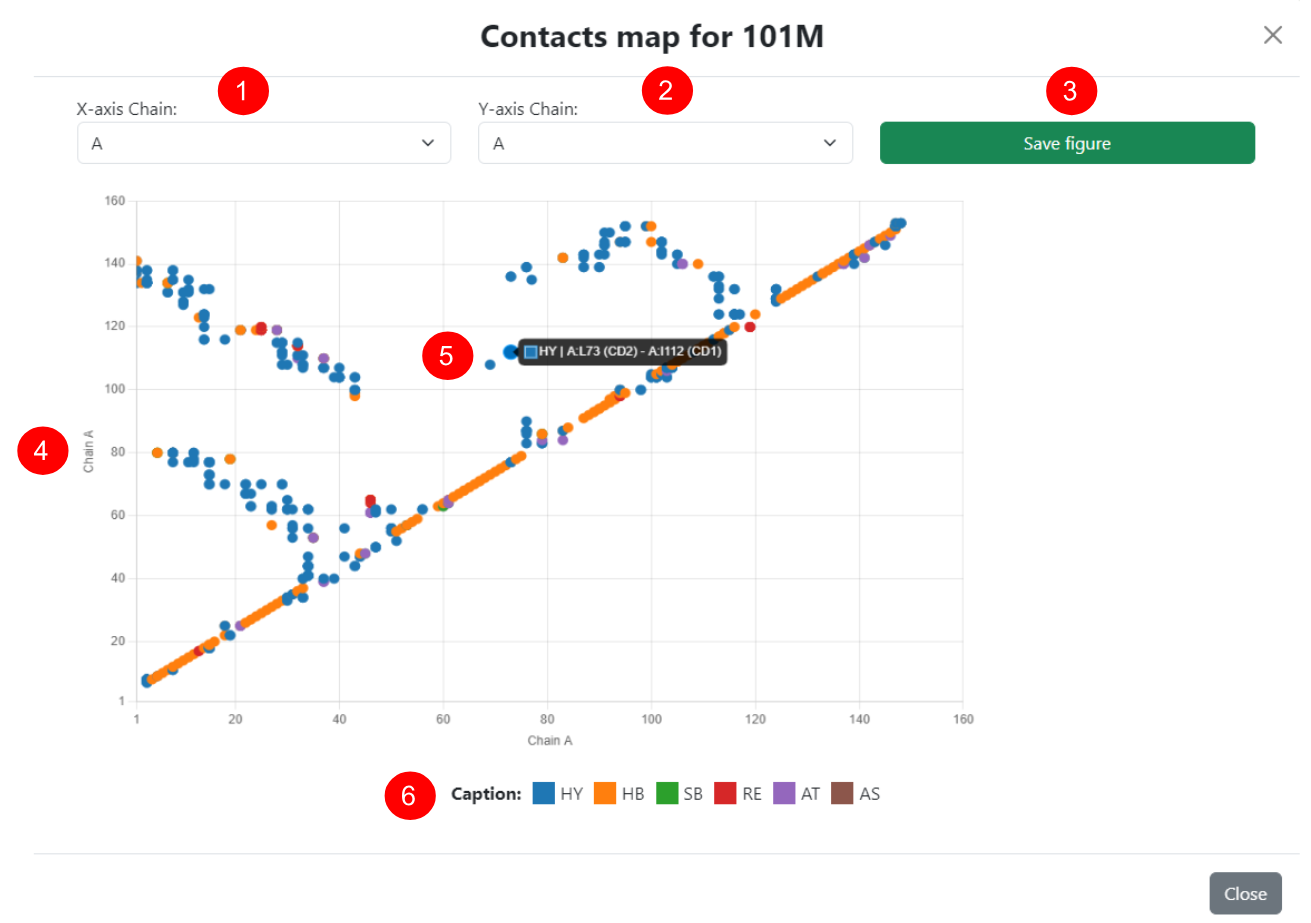

Contact Map

Next to the download button on the results page, the user can view the protein contact map in an interactive pop-up window. Since this is a two-dimensional representation of a protein's contacts, each axis of the map represents a polypeptide chain, both of which can be dynamically adjusted (1 for the X-axis and 2 for the Y-axis). In this way, inter-chain contacts can be visualized by selecting different chains in the menus, and the maps can also be saved in ".png" format (3).

In the interactive view of the selected pair of chains (4), the colors of each contact represent the predominant type for each pair of residues shown, according to the legend at the bottom (6). Additionally, each point on the map can be examined in detail using the cursor (5), where complete information about all contacts made by the selected pair of residues is displayed.

Types of Bonds and Interactions used in COCαDA-web

Disulfide Bonds

Disulfide bonds are one type of covalent bonds present in proteins, yet they are still weaker than peptide bonds. Formed exclusively by the sulfur atoms of the thiol (-SH) groups from a pair of cysteine residues, disulfide bonds are extremely important in the folding process and stability of certain proteins (Sevier2002).

Since the intracellular environments of living organisms are predominantly reducing, proteins containing disulfide bridges tend to be unstable in the cellular cytosol. As a result, the formation of these bonds typically occurs in specific regions and in the presence of catalysts, such as the endoplasmic reticulum in eukaryotes, the periplasm in prokaryotes, and the intermembrane space in mitochondria (Sevier2002, Hatahet2010).

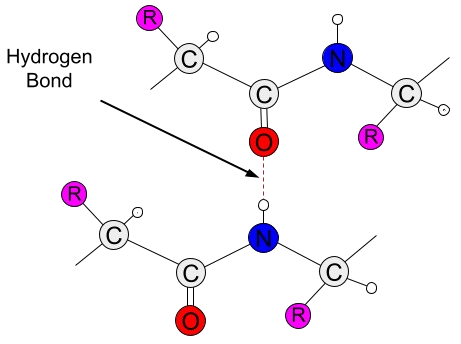

Hydrogen Bonds

Hydrogen bonds are a type of weak, short-range interaction that can occur between atoms of amino acid residues, playing an essential role in the folding process and functionality of proteins (Saenger1994, Agostini2019). With an electrostatic component, hydrogen bonds arise due to the difference in electronegativity between hydrogen atoms and other more electronegative atoms. In the case of amino acids, the only two atoms electronegative enough are oxygen (O) and nitrogen (N), both of which are key components of amino acids (Nelson2012).

When covalently bonded to one of these atoms, the hydrogen atom's electron cloud shifts toward the bond, creating two poles of opposite charges between them. Due to the partial charge generated on the hydrogen atom by this shift, it can then interact with another electronegative atom that has a partial negative charge. This third atom is called a hydrogen acceptor and forms a weak, attractive bond with the hydrogen atom (Nelson2012, Kessel2018). In addition to occurring between amino acid atoms themselves, hydrogen bonds can also be mediated by water molecules, which make up nearly the entire volume of intra- and extracellular environments in vivo (Saenger1994).

Hydrophobic Interactions

Due to their side chains (-R), amino acids can exhibit polarity properties, making them either polar or nonpolar. In a protein, the combination of these characteristics generates hydrophobic (nonpolar) and hydrophilic (polar) regions within its structure (Camilloni2016). A chemical environment composed solely of water molecules features numerous hydrogen bonds between them, forming a stable structure (Levy2006). However, when any solute (such as a protein) is introduced into this environment, the resulting disturbance breaks hydrogen bonds among nearby water molecules, which then reestablish bonds directly with the solute (Dunn2010, Kessel2018).

Since these interactions can only occur between polar molecules, the nonpolar regions of a protein tend to aggregate within its structure to interact with each other, thereby avoiding contact with water molecules. These interactions between nonpolar molecules are known as hydrophobic interactions and are critically important for protein folding (Kauzmann1959, Pace2011).

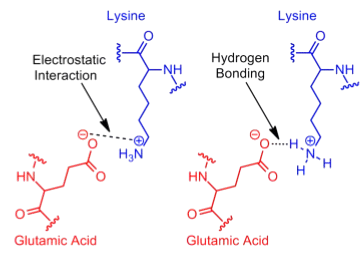

Electrostatic Interactions and Salt Bridges

Just like polar and nonpolar side chains, amino acids can also have charged chemical groups in their side chains. This is the case for lysine (K), arginine (R), and histidine (H), which carry positive charges, as well as aspartic acid (D) and glutamic acid (E), which also carry positive charges. Thus, amino acids with the same charge on their side chains form a repulsive electrostatic interaction, whereas those with opposite charges form an attractive electrostatic interaction (Nelson2012).

The charges on the side chains of these five ionizable amino acids play various structural and functional roles, such as pH-mediated protein denaturation, ion transport across membranes, and metal binding (Zhou2018). Additionally, other neutral amino acids can be ionized through the addition of charged chemical groups, as seen in the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of serine (S), threonine (T), and tyrosine (Y) residues (Hunter2012).

Since electrostatic interactions are a broad category that includes even hydrogen bonds, the term "salt bridge" is commonly used to describe a specific type of attractive electrostatic interaction (Kumar1999, Sinha2002). In salt bridges, the interaction occurs exclusively between fully ionized side chain groups and is further defined as an attractive electrostatic interaction in which at least one of the heavy atoms is within hydrogen bond distance (Donald2011).

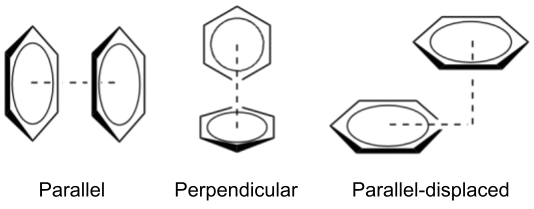

Aromatic Stackings

Aromatic stacking occurs exclusively between molecules that contain aromatic groups, also known as aromatic rings. In proteins, these groups are present in three amino acids: phenylalanine (F), tyrosine (Y), and tryptophan (W). The aromatic rings of these amino acids are composed of conjugated double bond systems, in which the electrons of the π orbital are delocalized, providing resonance and stability to the system (Kessel2018).

When two aromatic rings interact directly, this is known as π–π stacking, which can be further classified based on the geometry of the interaction (Smith2007). The simplest form is called "face-to-face" (or parallel), where the rings align in a parallel fashion. However, due to the repulsive nature of π-orbital overlap, the parallel geometry is relatively rare (McGaughey1998). The most common interaction patterns are "perpendicular" (T-shaped) and "parallel-displaced", both of which have attractive character (Martinez2012).

References

Agostini, A., Meneghin, E., Gewehr, L., Pedron, D., Palm, D. M., Carbo- nera, D., Paulsen, H., Jaenicke, E., and Collini, E. (2019). How water-mediated hydrogen bonds affect chlorophyll a/b selectivity in Water-Soluble chlorophyll protein. Sci. Rep., 9(1):18255.

Camilloni, C., Bonetti, D., Morrone, A., Giri, R., Dobson, C. M., Brunori, M., Gianni, S., e Vendruscolo, M. (2016). Towards a structural biology of the hydrophobic effect in protein folding. Sci. Rep., 6(1).

Donald, J. E., Kulp, D. W., e DeGrado, W. F. (2011). Salt bridges: geometrically specific, designable interactions. Proteins, 79(3):898–915.

Dunn, M. F. (2010). Protein-Ligand Interactions: General Description. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK.

Hatahet, F., Nguyen, V. D., Salo, K. E. H., and Ruddock, L. W. (2010). Disruption of reducing pathways is not essential for efficient disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm of e. coli. Microb. Cell Fact., 9(1):67.

Hunter, T. (2012). Why nature chose phosphate to modify proteins. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., 367(1602):2513–2516.

Kauzmann, W. (1959). Some factors in the interpretation of protein denaturation. In Advances in Protein Chemistry, Advances in protein chemistry, pages 1–63. Elsevier.

Kessel, A. and Ben-Tal, N. (2018). Introduction to proteins: Structure, function, and motion. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Philadelphia, PA.

Kumar, S. e Nussinov, R. (1999). Salt bridge stability in monomeric proteins. J. Mol. Biol., 293(5):1241–1255.

Levy, Y. and Onuchic, J. N. (2006). Water mediation in protein folding and molecular recognition. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 35(1):389–415.

Martinez, C. R. and Iverson, B. L. (2012). Rethinking the term “pi-stacking”. Chem. Sci., 3(7):2191.

McGaughey, G. B., Gagn´e, M., and Rapp´e, A. K. (1998). Π-stacking interactions. J. Biol. Chem., 273(25):15458–15463

Nelson, D. L. and Cox, M. M. (2012). Lehninger principles of biochemistry. W.H. Freeman, New York, NY, 6 edition.

Pace, C. N., Fu, H., Fryar, K. L., Landua, J., Trevino, S. R., Shirley, B. A., Hendricks, M. M., Iimura, S., Gajiwala, K., Scholtz, J. M., and Grimsley, G. R. (2011). Contribution of hydrophobic interactions to protein stability. J. Mol. Biol., 408(3):514–528.

Saenger, W. and Jeffrey, G. A. (1994). Hydrogen bonding in biological structures. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

Sevier, C. S. and Kaiser, C. A. (2002). Formation and transfer of disulphide bonds in living cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 3(11):836–847.

Sinha, N. and Smith-Gill, S. (2002). Electrostatics in protein binding and function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci., 3(6):601–614.

Smith, M. B. e March, J. (2007). March’s advanced organic chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, 6 edition.

Zhou, H.-X. and Pang, X. (2018). Electrostatic interactions in protein structure, folding, binding, and condensation. Chem. Rev., 118(4):1691–1741.